The global system for the production and consumption of clothing accounts for approximately 4 to 6% of global GHG emissions, equivalent to international flights and maritime shipping combined, and contributes 20% of industrial water pollution [1]. Clothing production doubled in the last 15 years due to fast fashion, with more than half going to landfills or incinerators in under a year. The negative environmental impact is set to triple by 2030 as production increases due to growing world population and rising incomes in emerging economies [2]. The global fashion industry must move from the linear take-make-waste system to a circular system, because making more clothes using virgin resources will not keep us within planetary boundaries of water use, CO2 emissions, use of chemicals and generation and disposal of waste [3]. A circular system designs out waste and pollution, keeps products and materials in use, and avoids the use of non-renewable resources and preserves renewable ones [4]. Large global fashion brands and retailers are moving towards circular economy business models [5]. The growing importance of circularity for global buyers poses many questions about how apparel global value chains (GVCs) will change and the implications for suppliers in the global South. CREATE examines the circularity shift in apparel GVCs and the challenges and opportunities it presents to Bangladesh’s apparel export industry.

Bangladesh will be affected significantly by the new demands of global buyers related to circularity, given that apparel exports contributed 84% of export earnings in 2019 and employed over 4 million people. Bangladesh was the second largest apparel exporter after China, but fell into third place in 2020 due to falling exports during the Covid-19 pandemic and declining competitiveness compared to Vietnam [6]. Large Bangladeshi textile and apparel firms have upgraded over the past ten years, moving into more complex products, diversifying into synthetic products and increasing the steps in the production that are carried out within their factories. However, the smaller firms that constitute the majority of the industry have not made these investments and produce basic products where there is high downward pressure on prices. Bangladesh’s apparel industry faces significant challenges as its preferential trade access to the European Union will end as it shifts to a middle-income country in the next few years, and buyers emphasize sustainable production and shorter delivery times in their sourcing decisions. Circularity offers an opportunity for the Bangladeshi industry to capture more value from its apparel exports and create more linkages between the apparel industry and the broader economy through waste management, recycling and innovations.

Existing research shows that low-income country governments promote apparel exports in order to access foreign exchange, knowledge and global market demand, but their apparel industries often become stuck in the parts of global supply chains characterized by low value capture [7]. Global brands and retailers based in the US, Europe and Japan captured a majority of the productivity gains in their supplier firms due to the asymmetrical market power of buyers [8,9,10,11]. In supplier countries where fabric is imported, few linkages emerged between apparel export industries and the rest of the economy. Countries with extensive cotton or polyester textile production experienced greater intra- and inter-industry linkages from raw materials to fabric to clothing, but design and especially branding remained with buyers, who captured more value due to intellectual property rights. Furthermore, the separation of innovation and market-facing activities, which take place in the global North, from production and routine services based in the global South, leads to thin industrialization in supplier countries because they experience growth in industrial output and exports without developing the corresponding system of innovation needed to support self-sustaining economic development [12].

The limits to economic upgrading in apparel supplier countries also apply to environmental upgrading. Increased pressure from NGOs and consumers regarding the negative social and environmental impacts of the fast fashion business model led global brands and retailers to adopt social, safety and environmental standards to mitigate reputational risks [13]. GVC scholars introduced the concept of environmental upgrading to examine how supplier firms could capture more value in global supply chains from changes that also reduced resource use, waste generation and biodiversity loss [14]. However, existing research on the apparel GVC shows that supplier firms covered the costs of meeting these environmental standards, with no price premium or other forms of financial support provided by their buyers [15,16,17]. Suppliers perceived these investments as necessary to retain market access, while buyers captured the value in terms of reputational enhancement and products marketed as sustainable. This was part of a broader trend where buyers used sustainability strategies to extract value but shifted the costs and risks to suppliers, resulting in a ‘sustainability-driven supplier squeeze’ [18].

Buyer initiatives regarding environmental standards did not address sustainability of the global value chain as a whole, and buyers continued with their fast fashion business models based on increased production and consumption. However, things are changing. A few large global fashion brands and retailers began making commitments in their corporate strategies to circularity, investing in new technologies, and adopting new business models. These brands and retailers were the pioneers, but other global buyers are quickly following suit, in response to growing consumer demand, financial activists putting pressure on shareholders and new and forthcoming EU regulations. Adopting a CE system in apparel supplier countries will allow supplier firms and their economies to tap into more value adding sources and activities.

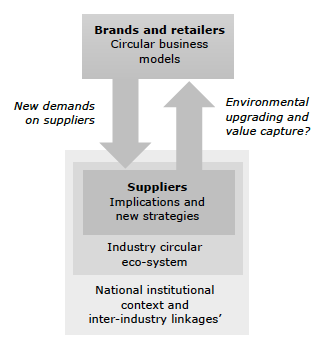

Scholars employing the GVC approach have demonstrated the limitations to industrialization through participating in global supply chains due to limited linkages with the domestic economy and value capture by buyers due to market power asymmetries and intellectual property rights. As a result, the GVC literature has come to rather pessimistic conclusions. CREATE contributes to moving the debate forward regarding how apparel supplier countries can overcome the limitations of thin industrialization and limited value capture, while minimizing their environmental footprint. The literature on environmental upgrading examines what drives supplier firms to pursue environmental goals and the kinds of competitive advantages that can be gained from them, but it does not conceptualize how supplier firms’ investments both minimize environmental impacts and result in higher value capture [14,19,20]. The project uses a conceptual approach that combines insights from the GVC approach and business systems, with insights from structural development economics and circular economy perspectives that focus on systems at the firm, sector and national economy levels (see Figure 1).

The GVC literature shows that buyers added more standards and shifted more tasks to suppliers, resulting in higher costs and risks born by suppliers, but did not always provide higher remuneration [8]. The business systems literature with GVC perspective argues that the nature of national institutional arrangements shapes suppliers’ capabilities and entrepreneurial vision, which in turn determines how and whether suppliers invest in upgrading [26]. The extent to which suppliers captured the gains from their upgrading depended on whether they could be easily substituted with other suppliers and how national and transnational institutions supported their upgrading and location-specific advantages. These dynamics of value capture apply to environmental upgrading, where the ability of suppliers to capture value from reductions in resource use and marketing products as sustainable depends on power relations within the GVC.

Suppliers can increase their bargaining power and thus capture more value if they develop capabilities that buyers come to depend on in their circular business strategies, making it more costly for buyers to switch suppliers [21]. This means that suppliers must participate in the innovations that make circularity possible: innovations in design that leads to greater sustainability during use and end-of-life disposal and in material production such as alternative cellulosic fibers or recycled fibers. These innovations can develop at the industry level through new firms that provide these innovations and inter-firm collaborations [34]. Developing a circular system in apparel production also involves closed-loop production in which waste is treated and returned into the production process and the use of new kinds of chemicals and treatments that produce less and less harmful waste, as well as industrial symbiosis in which waste is sold as an input into other manufacturing processes [33]. These processes require innovation in and complementarity with other industries and spur growth as each industry creates additional demand or new supplies and opportunities for other industries [22,23,24,25].

The existing literature shows that formal and informal institutions locked many Bangladeshi apparel suppliers into particular pathways [26]. Rather than invest in economic upgrading, many Bangladeshi supplier firms have focused on portfolio investments in unrelated industries, offsetting risk in case their activities in one sector failed. This growth path was common in other Asian countries during their early industrialization, where the government used industrial policies to compel them to invest in targeted sectors and build their capabilities while tolerating high profits and opportunistic behavior in other sectors [27,28].

References

- McKinsey & Company and Global Fashion Agenda. 2020. Fashion on Climate: How the fashion industry can urgently act to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, http://www2.globalfashionagenda.com/initiatives/fashion-on-climate/#/.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2017. A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future. http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundtion.org/publications.

- Global Fashion Agenda and The Boston Consulting Group. 2017. Pulse of the Fashion Industry, https://www.globalfashionagenda.com/publications-and-policy/pulse-of-the-industry/;

- Stahel, W. 2019. The Circular Economy: A User’s Guide. London: Routledge.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2020. Vision of a circular economy for fashion. http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundtion.org/publications.

- Berg, A., H. Chhaparia, S. Hedrich, and K-H. Magnus. 2021. What’s Next for Bangladesh’s Garment Industry, after a Decade of Growth? McKinsey and Company.

- Whitfield, L., K. Marslev and C. Staritz. 2021. Can Apparel Export Industries Catalyze Industrialization? Combining GVC Participation and Localization’, SARCHi Working Paper No 01-2021, South African Research Chair on Industrial Development, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. http://www.sarchi.ac.uj.za.

- Tokatli, N. 2013. Toward a better understanding of the apparel industry: A critique of the upgrading literature. Journal of Economic Geography 13(6): 993-1011.

- Mahutga, M.C. 2014. ‘Global models of networked organization, the positional power of nations and economic development’, Review of International Political Economy 21(1): 157.194.

- Palpacuer, F., P. Gibbon and L. Thomsen. 2005. ‘New Challenges for Developing Country Suppliers in Global Clothing Chains: A Comparative European Perspective’, World Development 33(3): 409–30.

- Anner, M. 2019. ‘Predatory purchasing practices in global apparel supply chains and the employment relations squeeze in the Indian garment export industry’, International Labour Review 158(4): 705-727;

- Sturgeon, T. and H. Whittaker. 2019. Compressed development, In Handbook on Global Value Chains (eds) S. Ponte, G. Gereffi, and G. Raj-Reichert. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 452–465.

- Lund-Thomsen, P. and A. Lindgreen. 2014. Corporate social responsibility in global value chains: Where are we now and where are we going? Journal of Business Ethics 123(1): 11-22. 14. De Marchi, V., E. Di Maria and S. Micelli. 2013. Environmental Strategies, Upgrading and Competitive Advantage in Global Value Chains, Business Strategy and the Environment 22(1): 62–72.

- Khattak, A., C. Stringer, M. Benson-Rea, and N. Haworth. 2015. Environmental upgrading of apparel firms in global value chains: Evidence from Sri Lanka, Competition and Change 19(4): 317–335.

- Goger, A. 2013. The making of a ‘business case’ for environmental upgrading: Sri Lanka’s eco-factories, Geoforum 47, 73–83.

- Khan, M., S. Ponte and P. Lund-Thomsen. 2020. The ‘factory manager dilemma’: Purchasing practices and environmental upgrading in apparel global value chains, Environment and Planning A 52(4): 766–789.

- Ponte, S. 2019. Business Power and Sustainability in a World of Global Value Chains. London: Zed Books.

- De Marchi, V., E. Di Maria and S. Ponte. 2013. The greening of global value chains: Insights from the furniture industry, Competition and Change 17(4): 299–318.

- De Marchi, V., E. Di Maria, A. Krishnan, S. Ponte, and S. Barrientos. 2019. Environmental Upgrading in Global Value Chains, In Handbook on Global Value Chains (eds) S. Ponte, G. Gereffi, and G. Raj-Reichert. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 310-23.

- Sako, M., and Zylberberg, E. 2019. ‘Supplier strategy in global value chains: Shaping governance and profiting from upgrading’, Socio-Economic Review 17(3): 687-707.

- Mathews, J. 2017. Global Green Shift: When Ceres meets Gaia. London: Anthem Press.

- Mathews, J. 2020. The Greening of Industrial Hubs: A Twenty-First-Century Development Strategy, In The Oxford Handbook of Industrial Hubs and Economic Development (eds) A. Oqubay and J. Y. Lin. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mathews, J., H. Tan, and M-C. Hu. 2018. Moving to a Circular Economy in China: Transforming Industrial Parks into Eco-Industrial Parks, California Management Review 60(3): 157–81.

- Mathews, J. 2020. Greening Industrial Policy, In The Oxford Handbook of Industrial Policy (eds) A. Oqubay, C. Cramer, H-J. Chang, and R. Kozul-Wright. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rana, M.B. and M. M. C. Allen. 2021. Why apparel suppliers are locked into the upgrading ladder in Bangladesh: an institutional and business systems perspective, In Rana, M. B. & Allen, M. C. (ed.) (2021) Upgrading the Global Garment Industry: Internationalization, Capabilities and Sustainability, Edward Elgar Publishing, UK.

- Lall 1992. Technological Capabilities and Industrialization, World Development, 20, 165-86.

- Amsden, A. and T. Hikino. 1994. Project Execution Capability, Organizational Know-How, and Conglomerate Growth in Late Industrialization. MITJP 94-12, MIT Japan Working Paper Series, Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Whitfield, L., Therkildsen, O., Buur, L., & Kjær, A. M. 2015. The Politics of African Industrial Policy: A comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- https://www.constructionweekonline.in/people/18114-2021-us-gbci-and-sala-recipients-announced

- https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/news/green-growth-campaign-action-oriented-approach-2101825

- https://textilelearner.net/green-garment-factories-in-bangladesh/; https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/news/circular-economy-rmg-reducing-and-reusing-waste-the-way-go-2047433

- Rana, M.B. and Tajuddin, S.A. 2021. Circular Economy and Sustainability Capability: A Case of H&M, In Rana, M. B. & Allen, M. C. (ed.), Upgrading the Global Garment Industry: Internationalization, Capabilities and Sustainability, Edward Elgar Publishing, UK.

- Sørensen, O. J. and Ngoc, N. B. 2021. Internationalization of Vietnamese Garment Manufacturers from an Innovation Perspective: Toward a U-Shaped Internationalization Path. Rana, M. B. & Allen, M. C. (ed.), Upgrading the Global Garment Industry: Internationalization, Capabilities and Sustainability, Edward Elgar Publishing, UK.